Feel free to share

Using this site means trees will be planted. ^.^

Using this site means trees will be planted. ^.^

(Find out more)

Map creation guide part 3: Nature

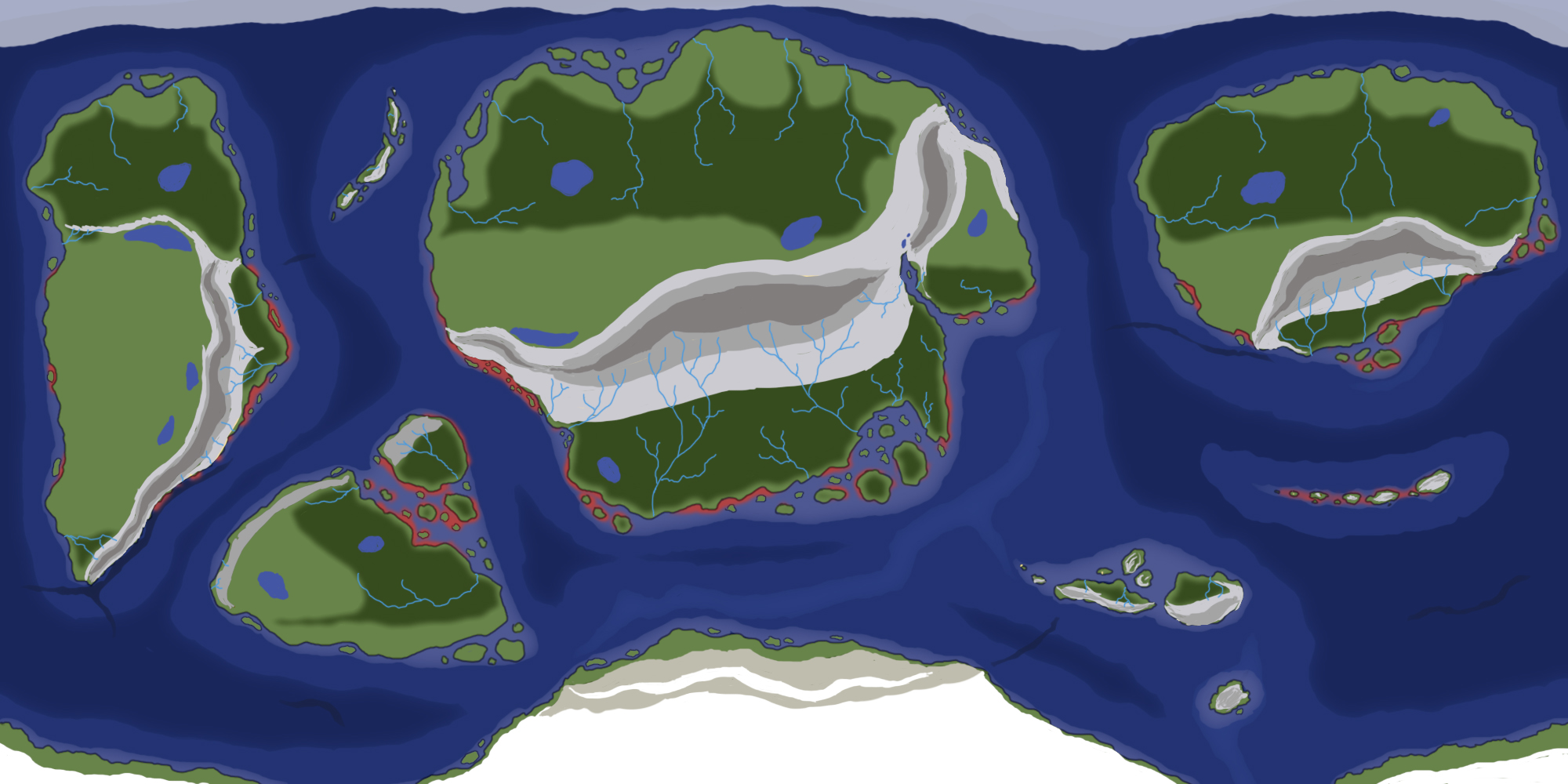

Time to add some natural elements to our map. I already added mountains at the start, but they were more like placeholders, so in this part we'll spice them up a little. I'll also go over how to add rivers, oases, mangroves, and a whole bunch more. But first I'll go over some the different biomes you'll find in the climate zones we covered in part 2, so you start to think about what each part of the world may look like.

This section will be very big, so let's delve straight into it.

- Biomes

- Tundra

- Boreal forests/taigas

- Montane grasslands & savannas

- Deserts & xeric shrublands

- (Sub)Tropical moist broadleaf forests

- (Sub)Tropical dry broadleaf forests

- (Sub)Tropical coniferous forests

- (Sub)Tropical grasslands, savannas & shrublands

- Mangroves

- Flooded grasslands & savannas

- Temperate grasslands, savannas & shrublands

- Temperate broadleaf & mixed forests

- Temperate coniferous forests

- Mediterranean forests & woodlands

- Coral Reefs

- Importance

- Land Features

- Aquatic Features

- Next Up: Making it look good

Biomes

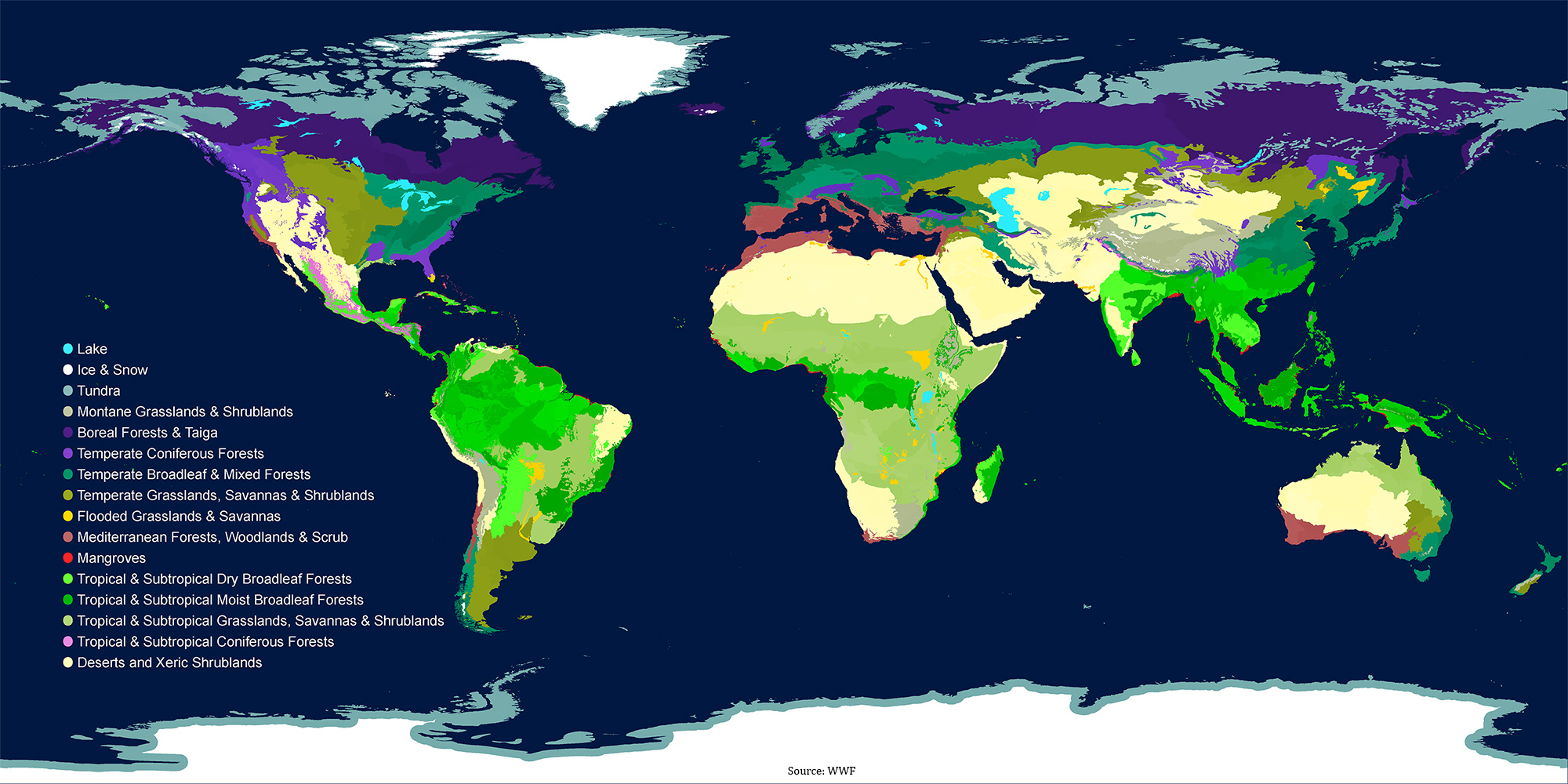

Biomes are distinct biological communities within a shared climate. They're similar to habitats, except that a biome can contain a whole range of different habitats. There are many different classification systems to map the Earth in a range of different biomes, but for this guide I'll be using the Global 200 system by the WWF.

As you can see, the map shares a lot of similarities with the climate zone map. However, the map above doesn't cover all the individual biomes, only the broad versions and only terrestrial ones. In actuality there are over 200 biomes, hence the Global 200 name.

As far as creating our map goes, we're not going to create a detailed map with all the biomes filled in, but we will create one with main features like rivers, specific mountain types and I'll cover how to organically add specific types of natural regions. The climate zone map will act as our guide, and the map's purpose and/or the story universe behind it will dictate where each biome is. Just as the Queensland tropical rain forests of Australia aren't the same as the rain forests in West Africa, so too would different regions of my map be different despite being the same biome classification.

But enough rambling, let's go over the biomes. We'll start at the poles again.

Tundra

Tundra biomes are essentially the same as the tundra climate zone. You'll find few trees, if any, and a landscape dominated by dwarf shrubs, grasses, small plants, mosses and lichens, assuming vegetation is able to survive. If not, you'll generally find a rocky landscape of frozen soil.

Tundras are often dry and very windy, but lakes are able to form in summer when the ice melts. Despite there being very little rain, the frozen soil beneath the ground prevents water from running off, so melting ice turns to marshes and lakes.

Biodiversity is incredibly low in tundras. In the Northern Hemisphere, only 48 species of land mammals can be found. There are no land mammals in the Antarctic tundra, but marine mammals do inhabit the lands periodically.

Whales, seals, penguins, a range of birds (often migratory), reindeer, arctic hares and foxes, polar bears and lemmings are some examples of animals found in tundras, though obviously not across all of them.

Any mountain on Earth could also be home to a tundra as long as it's high enough. When elevations are high enough, the cold and strong winds prevent trees from being able to grow. The elevation required changed depending on how far away you are from the equator. On Earth this means 3500-4000 meters / 11,500-13,100 ft between 30 degrees north and 20 degrees south. Moving further from the the zone, toward the poles, you can subtract 130 meters / 430 ft, per 1 degree extra (so 31 degrees north would mean 3370-3770 meters, and so on). Once you reach 50 degrees north or south, you only need to subtract 75 meters / 245 ft per degree further toward the poles.

Boreal forests/taigas

Boreal forests, also known as taigas, are biomes characterized by their forests consisting of primarily pines, spruces and larches. But you may also find small-leaved deciduous trees, like alders, birches, poplars and willows in areas without extreme winter colds. On the parts furthest away from the poles you may also find elms, limes (not the fruit ones), maples and oaks.

These latter parts are usually home to closely spaced trees within their forests, leading to forests with a closed canopy. As a result you'd find almost exclusively moss growing on these forest floors.

Closer to the poles the forests are less densely packed and the ground's covered primarily in lichen. Trees here are also often pruned on the windward side due to ice and snow particles slowly picking away at the tree at the hands of the strong winds.

Boreal forests are also home to various berries (including cranberry and wild strawberries), as well as ferns and grasses.

Wildfires happen every 20-200 years, which clears the canopy and allows light to peak through, which in turn allows the before mentioned plants to flourish, among others.

Boreal forests support a small range of animals, oddly enough this includes a few amphibians who are able to handle the cold just well enough.

Fish and bird species are more common, though many are migratory. Fish include trouts, pikes, salmon, whitefish and lamprey. Birds include ravens, eagles, sparrows and grouses.

Mammals are few and far between. Canada's boreal forests support 85 mammal species, for example. Mammals you may find in Earth's boreal forests include moose, reindeer, otters, wolverines, badgers, weasels, wolves, coyotes, bears, tigers, lynxes, bisons, squirrels, hares and beavers.

Montane grasslands & savannas

Montane grasslands & savannas are high altitude biomes found in tropical, subtropical and temperate climates. At latitudes closer to the poles or very high altitudes you'd find tundras instead.

As the name suggests, these biomes are dominated by grasses. The more rainfall, the taller the grass species usually are. Unlike tropical savannas, trees are rarely found in this type. Shrubs are slightly more common, though not necessarily present in every biome of this type.

Biodiversity is relatively low due to the scarcity in resources. Larger animals often migrate huge distances after eating the grass in one place, and predators follow as a result. Unlike the tropical savannas who cover enormous amounts of relatively flat land, the montane grasslands and savannas are smaller in size and generally undulating thanks to their altitudes. As such, you won't find the same gigantic herds of herbivores either.

Biodiversity can be a lot higher in regions of relatively narrow strips of montane grasslands surrounded by biomes with a richer diversity of life. Border zones between biomes are often hot spots for biodiversity, and the montane grasslands and savannas are no exception.

Animal species antelopes, zebras, elephants, lions, cheetahs, buffaloes, monkeys, bats, birds, frogs, toads, snakes, hogs, and more.

Deserts & xeric shrublands

This biome type covers 19% of Earth's land surface and is therefore the largest terrestrial biome today. Temperature extremes are the main characteristic often resulting in a low biodiversity for the majority of the time. However, when rain does fall, biodiversity can explode and deserts can transform incredibly quickly into lush landscapes, only to then return back to a barren landscape until the rains return once more.

Flora and fauna who persist through the driest parts of the desert's season have all evolved to deal with water scarcity. Camels, cacti and woody stemmed shrubs are only a few examples of this.

Not all eserts and shrublands have low biodiversities. A great example of this are the Madagascar spiny forests, and the Sonoran Desert in Arizona and California.

As far as animals go, you may find scorpions, snakes, tortoises, iguanas, lizards, ants, bees, spiders, vultures, owls, hawks, bobcats, coyotes, mice, rabbits, armadillos, hyenas, lions, camels, antelopes, and more.

(Sub)Tropical moist broadleaf forests

This biome is found around the equator and can stretch up to about 30 degrees north and south if conditions are right. They're characterized by low variations in temperature and huge amounts of rainfall. This biome consists of tropical rainforests, montane rainforests, flooded forests and evergreen rain forests, and are thus usually found within tropical rainforest climate zones. They can also be found in monsoon and wet savanna climate zones if conditions are right.

This biome is home to the highest biodiversity of any biome and plant growth can be explosive as a result of its high levels of rainfall. A tree could grow 23 meters / 75 feet in just 5 years, for example.

Half of the world's species is thought to be home to this type of biome, which includes a wide variety of apes, monkeys, snakes, big cats, deer, insects, spiders, birds, frogs, fish, turtles, sloths, bats, elephants, rhinos, buffaloes, bears, and much, much more.

Tree and plant species are even more numerous and many have yet to be discovered. A square kilometer of rainforest is often home to 1000 tree species, and the total in the Amazon rainforest is thought to be in the range of 16000. Plants far exceed this number, of course. Orchids alone have over 25000 species.

(Sub)Tropical dry broadleaf forests

This biome is found around 10-20 degrees north and south of the equator, but can stretch further in both directions if conditions are right. As a result they're often found in monsoon and savanna climates, as well as tropical rainforest climates. Unlike the previously mentioned moist version, this biome has a dry season, which impacts wildlife throughout this biome.

Trees are often deciduous and will lose their leave during the dry season, which means light can reach the ground beneath them and allow other species to flourish.

Riparian zones are a common feature as a result of these dry periods as well. Riparian regions are the borders of water, both flowing (rivers, etc.) and none flowing (lakes). In these riparian zones, trees are often evergreen. So during the dry season the contrast becomes stark.

Infertile spots, often a result of human interference, are also home to these evergreen trees.

Biodiversity is generally very high, though not as high as the moist version of this biome. But the species that do exist tend to spread further than their moist counterparts due to less competition.

As far as animals go, you'd find many of the species mentioned in the moist version, just in a smaller variety.

(Sub)Tropical coniferous forests

As the name suggests, this biome consists of many species of coniferous trees. They're found in regions with little temperature variation and little rainfall. On Earth these regions are all on the northern hemisphere, primarily in Central America and in parts of the Himalayas.

These forests are often dense and have a closed canopy, so little light is able to reach the floor. As a result you don't find much ground flora beyond species of ferns and fungi. Small trees and shrubs are still found in the understory of the forest, however.

As far as animals go, migratory birds and butterflies call this biome their home during the winter. Throughout the year you can also find tigers, leopards, antelopes, pheasants, partridges, rats, lizards, turtles, bats, bears, wolves, snakes, rabbits and mice. However, it's not uncommon for there to be little to no mammals at all, or only mammals introduced by humans within these regions.

(Sub)Tropical grasslands, savannas & shrublands

Another very large biome, which covers the majority of Africa and big parts of Australia and South America, though they feature on every continent except for Antarctica. Like the montane grasslands and savannas, this biome is dominated by grasses and shrubs. But trees are found as well, though they grow sparingly and usually have a way to preserve water in the dry season. Acacia trees lose their leaves, for example, and boabab trees store water in their thick trunks.

Rainfall is incredibly season dependent, with some regions receiving all of their yearly rain within a few weeks. As a result, flora can explode for a short period before diminishing again until the next rain season. This also makes for a harsh ecosystem, as severe droughts could lead to mass deaths.

Despite the fact competition for resources increases the more time has passed since the last rains, huge herds of animals are often found chasing rains and grasses while being hunted by predators and their numbers are able to be fed for most of the season.

Animals include wildebeests, zebras, gazelles, buffaloes, lions, cheetahs, leopards, hyenas, wild dogs, rhinos, elephants, giraffes, vultures, cranes, parrots, monkeys, lizards, tortoises, crocodiles, and a whole lot more.

Mangroves

Mangroves are found in tropical and subtropical climates, always along coastal regions where sediment is deposited (like at the end of a river). As a result, mangroves are full of flora able to survive and thrive in saline water. This can range from brackish water to ocean water to water twice as salty as ocean water because of evaporation. This also means biodiversity, in terms of flora, is very low.

Mangroves offer homes to crustaceans, young fish and all sorts of other animals able to climb, crawl or fly through the thick canopies and roots. Animals include monkeys, birds, reptiles and in some cases sharks and even tigers.

Mangroves also protect coastal regions against erosion, offer a buffer in cases of heavy storms and hurricanes, filter out debris from the water thanks to their thick root network, and mangrove trees store more carbon than regular trees, which could be of importance within your story universe.

Flooded grasslands & savannas

As their name implies, these biomes either flood periodically or are permanently flooded. Some are a combination of both, with a bigger portion flooding during the rainy season. Examples include the Everglades in the US and the Pantanal in Brazil.

Any flora is obviously water loving or water resistant, so you'll find many reeds, grasses and mangrove trees in the right climate zones. In some parts of these biomes you may also find forests, including pine forests, but they grow only on non-flooding pieces of land within this biome.

Note that this biome doesn't include all forms of wetlands. Peat swamps, regular swamps, and so on can form across the world in all sorts of different biomes. The main focus in the flooded grassland & savanna biome is their biodiversity and role for migratory birds. Speaking of which, this biome is home to a huge variety of species and, during the right season, countless migratory birds seeking refuge and food within these rich waters.

Among the reeds, grasses, shrubs and even mangroves, you may find nesting birds, hunting crocodiles, snakes, large mammals, frogs, countless butterfly species and many different fish species.

Temperate grasslands, savannas & shrublands

Like the (sub)tropical version, this biome features almost exclusively grasses and short shrubs, but alongside river banks you may find trees and other, larger flora. As their name implies, they're only found in temperate parts of the world, which also means their temperature differences are greater than (sub)tropical versions, and their maximum temperature is lower.

They are able to support huge herds of grazing animals and the predators who prey on them, as well as various bird species, burrowing mammals and countless insects.

Flower species can be incredibly numerous, which in turn supports a greater diversity of insects and small animals. But this also means these biomes are incredibly fragile. Farming, freak weather, climate change and other elements can have huge impacts on biodiversity and survival of species within this biome.

In terms of animals, you may find bison, antelopes, bats, squirrels, gophers, deer, elk, lizards, snakes, pumas, foxes, and more.

Temperate broadleaf & mixed forests

These forests usually have 4 layers: a canopy of full-sized trees, a lower layer of less matures trees, a shrub layer and a ground layer. Unlike their (sub)tropical counter parts, temperate forests have the highest biodiversity on the ground and shrub layers.

The same tree genus are found across most temperate forests around the globe, but with different localized species. Dominant trees include maples, beech, oaks, birch and more.

Many species rely on late-succession forests, meaning forests with many mature trees. Combined with the slow growth rate of temperate forest trees, this can make the destruction of even partial forests disastrous for many species. Many understory species are unable to spread without the protection of the mature canopy species, for example.

The loss of major predator species like wolves also lead to a drastic change in the structure and biodiversity of these forests.

In terms of species you may find countless lichens, flowers, herbaceous plants, brambles, beavers, birds, deer, amphibians and reptiles, squirrels, hares, bats, bears, leopards, cougars, wolves, and lynxes.

Temperate coniferous forests

These forests are found on coastal areas with warm summers and cool, wet winters, as well as on mountain slopes further inland. Evergreen trees obviously dominate these, but can range form needleleaf trees to broadleaf evergreens, with some deciduous trees (oaks, hazel, birch, etc.) mixed in at times as well.

These forests often only have 2 layers: the overstory and understory, but a shrub layer could be found as well. It's common for one type of tree to dominate these forests though, like the redwoods, sequoia and ash forests found in the Americas.

In the wetter versions, the shrub layer usually contains many ferns and flowering plants, while the dry versions are often dominated by grasses and some flowering plants. These dry versions are vulnerable to forest fires, but these fires are an important part of the natural cycle here.

Animals found could include deer, moose, various rodents, birds, butterflies, leopards, bears, foxes, snakes, frogs, goats and wolves.

Mediterranean forests & woodlands

These forests obviously occur in the Mediterranean Basin, but can also be found in southwestern Australia, parts of Chile, parts of South Africa and parts of California.

Their summers are hot and dry, and their winters mild and wet. But this biome can also occur in climates with more uniform rainfall throughout the year.

Fires are common and an important part of the natural cycle. Many trees and plants are fire-loving in the sense that they depend entirely on fire for reproduction, the cycling of nutrients or the removal of species for their personal gain. This usually leads to a mosaic-like landscape where different parts are covered in different stages of growth, further fueled by differences in terrain, sun exposure, and so on.

Oaks, walnuts and pine trees are common, as are Eucalpytus trees in Australia and beeches in Chile. However, forests are usually only found along riparian zones (the borders of rivers/lakes/etc.). Grasslands and shrublands usually dominate, but many of them have been converted to farmland due to their rich soils.

This biome is often a hotspot for biodiversity. Besides the thousands of plant and tree species, animals include lynxes, countless reptiles and insects, various rodents, a wide range of bird species, deer, monkeys, leopards, boars, goats, bears and more.

Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are among the most diverse ecosystems found on Earth and play an important role in many aspects of life ranging from tourism to food, from shoreline protection to providing habitats, and much more.

Coral reefs are most commonly found in ocean waters with few nutrients and the majority of corals require water around 27 degrees C (81 degrees F), but you can find corals in much colder waters too.

They're usually found at depths no deeper than 50 meters (160ft), but specialized corals can be found far deeper than that in micro-climate zones and other regions of the ocean.

We'll be adding corals to our map further down in this guide.

There are a variety of reef types, which are as follows:

- Fringing reefs: They're the most commonly found reefs, and are simply corals growing on shores. They continue to extend towards the sea and thus get thicker/longer as they go, creating a wedge shape.

- Barrier reefs: Very rare as they take forever to develop. Are thought to develop as a result of rising sea levels or sinking sea beds. They're separated from shores by a lagoon.

- Platform reefs: Grow wherever the seabed is close enough to the surface to provide the conditions corals need to grow. They can be found thousands of kilometers/miles from the coast, though this is rare.

- Atolls: Atolls are rings of corals (or sometimes U-shapes), usually formed when corals grow around a volcanic island, which then erodes to below sea level.

- Cays: These are sandy islands on top of a coral reef. As a result, much of the sediment on these islands are skeletal remains of the surrounding reef.

- Others: There are some other types, but they're usually small, part of the previous types and/or rare. They can be worth looking into if you want more coral details in your world though.

Summary table

| Biome | Location | Flora | Fauna | Extra |

| Tundra | High mountains and near poles | Tiny shrubs, grasses, moss & lichens | Whales, seals, birds, reindeer, arctic hares. | Very low biodiversity. |

| Boreal forests/taiga | Near poles | Small-leaved deciduous & coniferous trees | Moose, deer, wolves, bears, rodents, birds. | Forest fires every 20-200 years. |

| Montane grasslands & savannas | High altitudes in (sub)tropical & temperate climates | Many grasses and shrubs. Rarely any trees. | Antelopes, elephants, monkeys, bats, reptiles, hogs, lions. | Biodiversity relies on richer, neighboring biomes. |

| Deserts & xeric shrublands | Extreme temperature zones with little water. | Cacti and woody shrubs. | Camels, scorpions, reptiles, birds, rodents, hyenas. | Often highly adapted species. |

| (Sub)Tropical moist broadleaf forests | Around the equator in zones with lots of rain. | Countless species. Many still undiscovered. | Apes, monkeys, reptiles, deer, insects, birds, elephants, bears. | Incredibly high biodiversity. |

| (Sub)Tropical dry broadleaf forests | Near equator, but usually not on it. | A wide variety of deciduous and evergreen trees (depending on micro-climates) | Same as moist broadleaf, but in smaller quantities & varieties. | High biodiversity |

| (Sub)Tropical coniferous forests | Regions with little rainfall and little temperature variation. | Coniferous trees in large quantities (so a closed canopy). | Tigers, leopards, antelopes, birds, reptiles, bears, rodents. | Common to find no mammals at all. |

| (Sub)Tropical grasslands & savannas | Within the (sub)tropics of course. | Dominated by grasses and shrubs, but trees found here and there. | Huge herds of wildebeest, zebras, buffaloes, gazelles. Lions, hyenas, elephants and more. | Animals follow the rain. |

| Mangroves | Along coasts in (sub)tropical climates. | Mangrove trees and other water-loving flora. | Fish, crustaceans, monkeys, birds, sharks, tigers, reptiles. | Act as storm buffers. |

| Flooded grasslands & savannas | Temperate to tropical zones. | Reeds, grasses, water plants, mangrove trees. | Countless birds, crocodiles, snakes, frogs, butterflies, large mammals. | Can be seasonal or continuous. |

| Temperate grasslands & savannas | In temperate zones of course. | Countless flowers and grasses, with some shrubs. | Butterflies, insects, birds, grazing animals, burrowing mammals. | Fragile. |

| Temperate broadleaf & mixed forests | Temperate zones as the name implies. | Oaks, maples, birches, beeches, various shrubs and flowers on the lower layer. | Bears, leopards, cougars, wolves, deer, beavers, reptiles, rodents. | |

| Temperate coniferous forests | Also in temperate zones. | Evergreen trees (both broad- and needleleaf), and some deciduous trees. | Deer, moose, leopards, wolves, goats, reptiles, rodents. | |

| Mediterranean forests | Often in areas with hot summers and wet winters, like the Mediterranean Basin. | Oaks, beeches, eucalyptus, shrubs, grasses, heat-loving flora. | Deer, boars, leopards, goats, bears, birds, reptiles, insects. | Fires are common. Many plants and trees rely on it for reproduction. |

| Coral reefs | Most commonly in warm waters (between 30 degrees north and south) with few nutrients. | Few flora, since corals are fauna. But seagrass, algae and mangroves could be found. | One of the most biodiverse regions in the world. | Fragile to changes in ocean temperatures and salinity. |

Importance

That was a big chunk of information, and it only scratches the surface of each biome too. While the information covered might not be of importance to everyone, I thought it was worth adding for those it is important to. For a story universe, this information would potentially be very important, for example.

But the information above can also help shape the way we design our map. Rivers are different in each biome, so choosing whether we add 1 or multiple rivers in a specific area could make a huge difference if you follow it up with riparian zones, settlements built along this river, and so on.

But enough on this, let's get back into adding stuff on our map again.

Land Features

Let's start with land features, which, for this section, means features found on land. So I'll cover rivers and other aquatic features like this as well, but not coral reefs, oceanic trenches, and so on.

Rivers

Since rivers dictate a huge amount of the world in terms of both natural and human elements, they're a good one to start with.

First, how do rivers work? They obviously flow from high altitudes to lower ones, and generally start in mountains. They also take the shortest (steepest) route possible.

Smaller rivers often join together and become one larger river. Larger rivers rarely split up into smaller rivers, but off-shoots can happen on rare occasions where erosion leads to new openings for water to flow more efficiently from high to low. These off-shoots are often temporary as further erosion will usually make the new path the one and only main path in the future. Temporary is relative though, we're talking about natural processes after all, not human life.

For the purposes of map creation, we'll only focus on major rivers rather than trying to create a map of all the tiny rivers that flow everywhere for short distances before joining up with the main rivers. This gives us the freedom to add those if the need arises at later dates, like when we want to add a settlement somewhere as they're usually built alongside rivers throughout history.

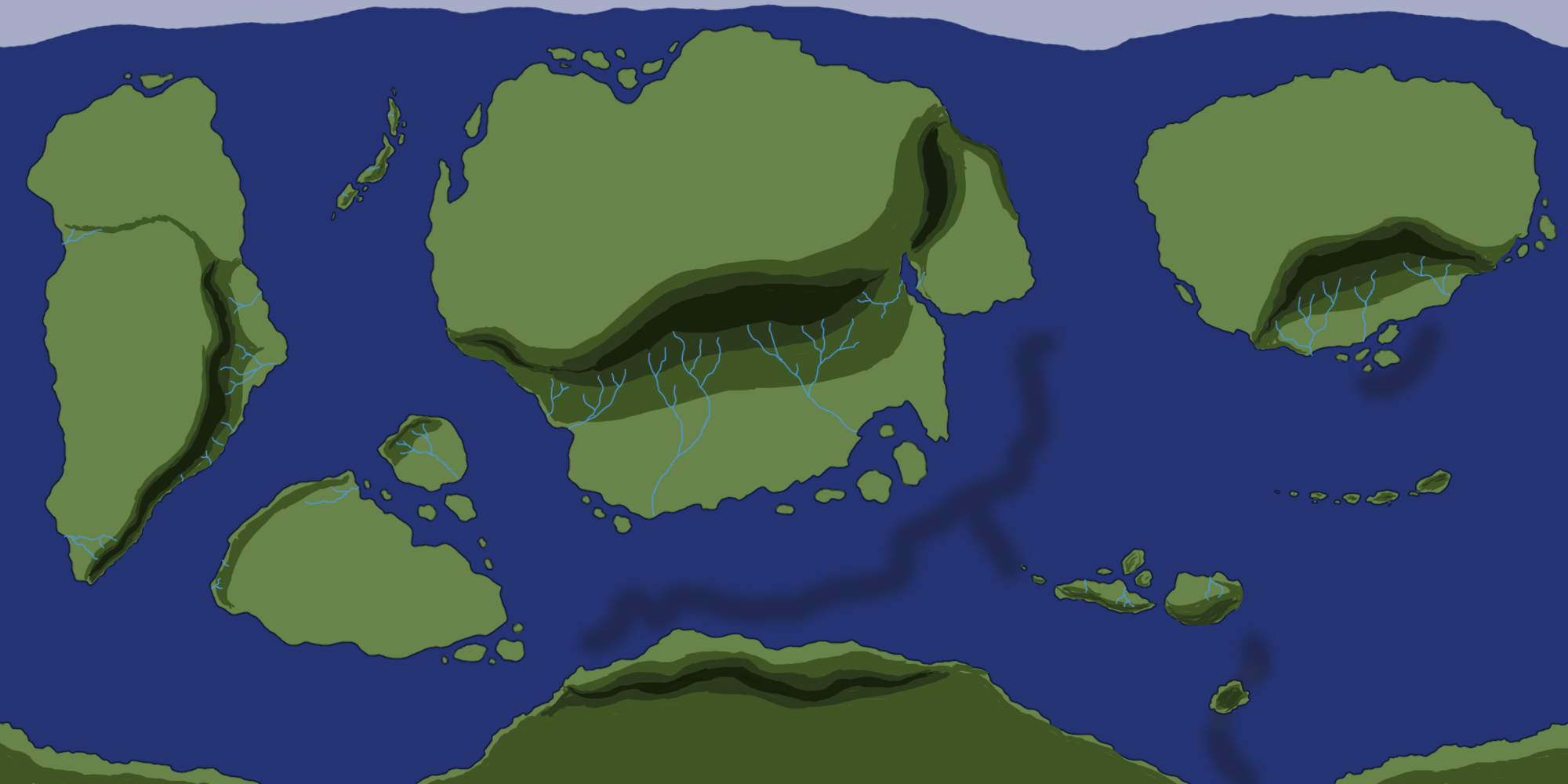

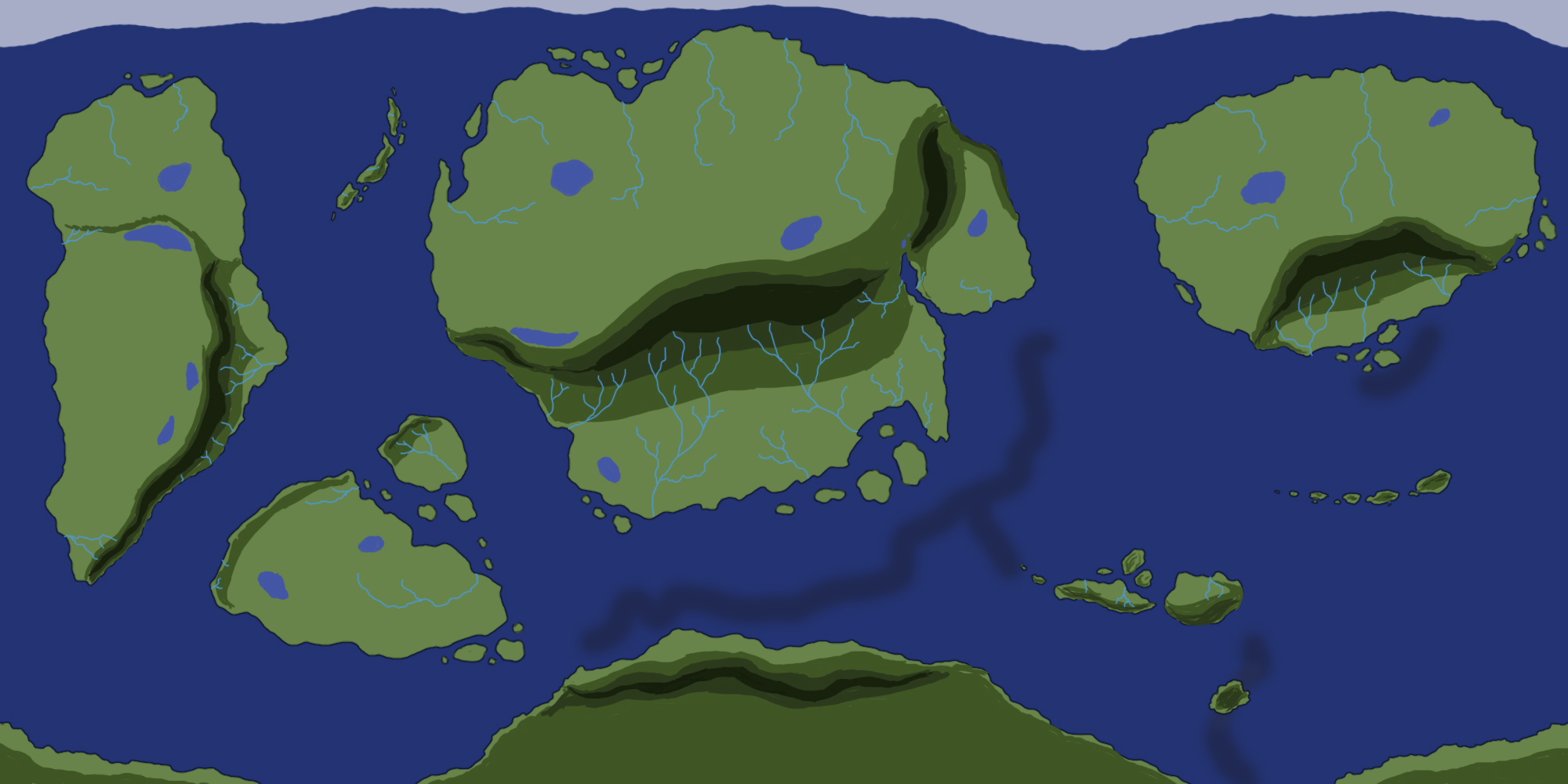

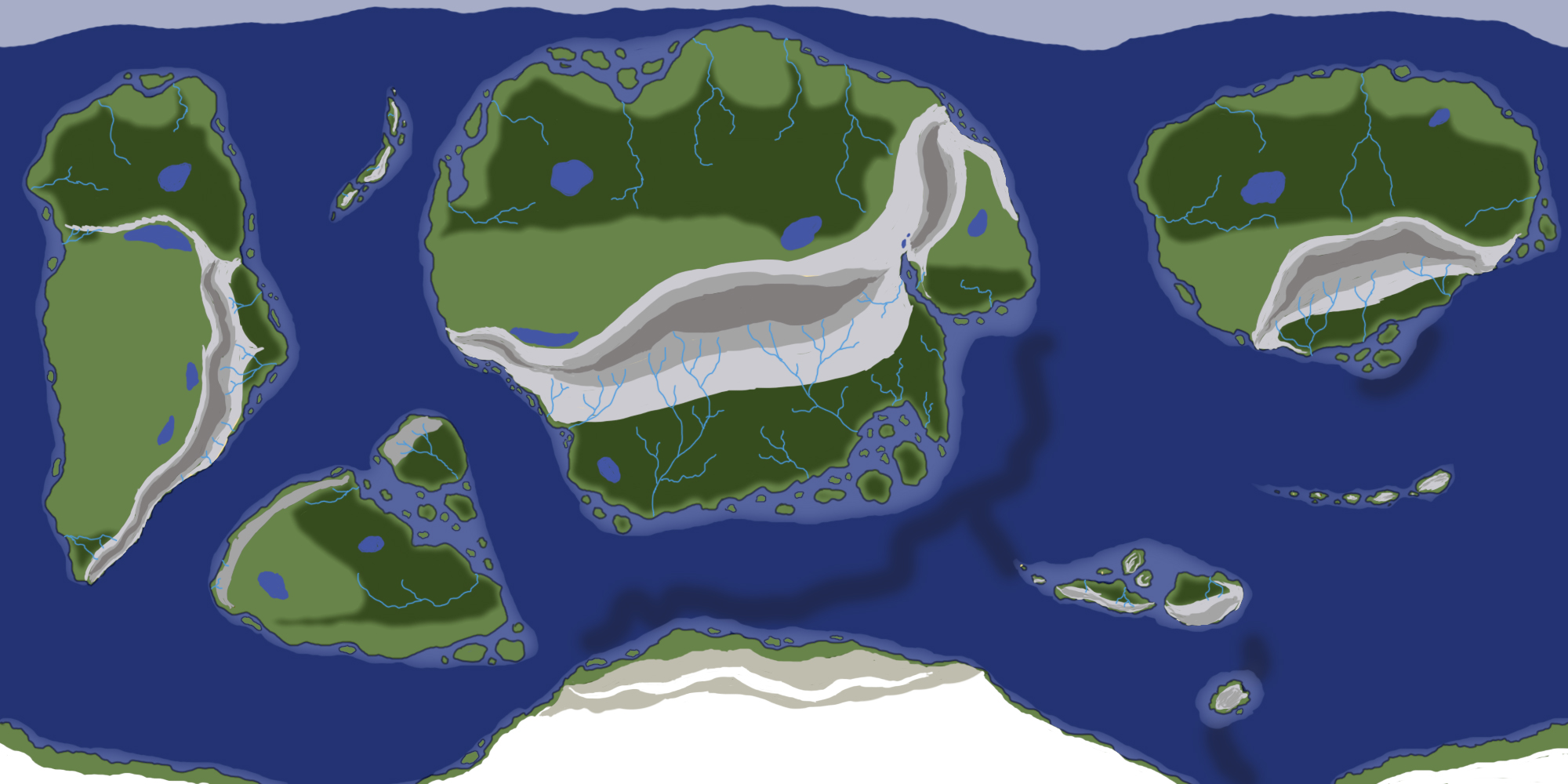

I started with creating rivers going from the highest mountain tops in regions with plenty of rain, but included a few smaller rivers in regions outside of the tropical regions too. But rivers don't only form high up on these types of mountains nor only in regions with huge amounts of rainfall. Any region higher than sea-level with enough rainfall (or snow) can have a river, but, as mentioned, we're only focusing on main rivers. So for the next step I will keep in mind some of the information already covered (riparian zones within biomes, seasonal rainfall, biome requirements in general) as well as plans for the future, and then add more rivers accordingly.

As you can see, I've added a bunch of rivers in non-desert zones. You can have rivers in deserts (like the Nile), but my world's desert are locked between mountain ranges and oceans on most continents, so there's nothing to feed a river akin to the Nile in my world. I can still add tiny rivers, lakes/oases though, but I'll cover oases later.

I will also be refining the rivers in the details stage where I'll vary the thickness in some areas, add deltas, and so on, but you're free to add this already of course.

Things to note are:

- I didn't draw rivers in the highest parts of the mountains. A river's source is usually tiny streams slowly becoming a big one.

- More rain usually means more rivers and/or bigger rivers. But areas with very little height differences could have incredibly long, meandering rivers too.

- Placing a large marker to signify relatively elevated terrain at the start of each river can help create a makeshift elevation map to guide your decision on where to put other rivers.

There is a lot more to rivers ranging from annual rainfall to ground type to continent age to flora and much more, but I won't cover that in this part nor probably any other part. We'll see. For now, let's move onto lakes.

One final note, it's a lot easier to create rivers if you do a detailed height map first. The terrain will then dictate the only paths water could take downhill. I don't want to delve into the minute details and make map type after map type yet though, but I'll cover height maps in the future.

Lakes

There are millions upon millions of lakes around the world and there's a wide variety of lake types too, so covering everything on lakes is a bit much when all we want to do is create a map. Instead I'll delve into a few types you may find interesting to add to your map based on the largest and most world-altering lakes on Earth.

At a most basic form, there are 2 types of lakes: Ones without an outflow and ones with an outflow, but they're further subdivided. The ones without an outflow (endorheic regions) are usually self-sustaining (but obviously still change over time). Water will evaporate, turn to rain and fall somewhere around it, then seep back into the basin through ground water paths and streams. The Caspian Sea is a great example of this, which, despite its names, is considered the world's largest lake.

These lakes usually occur far inland and are often blocked by mountains on at least 1 side. They can occur in any climate, but are common in desert climates. Within desert climates the lakes might dry up completely until the next rainy season (could be very, very long before rain falls), which often leaves hard, salty surfaces and may never become lakes again due to a changing climate (like Death Valley).

For map creation purposes, you can put an endorheic lake pretty much wherever you want as long as they're unable to drain (so surrounded by higher elevation land) and far enough inland.

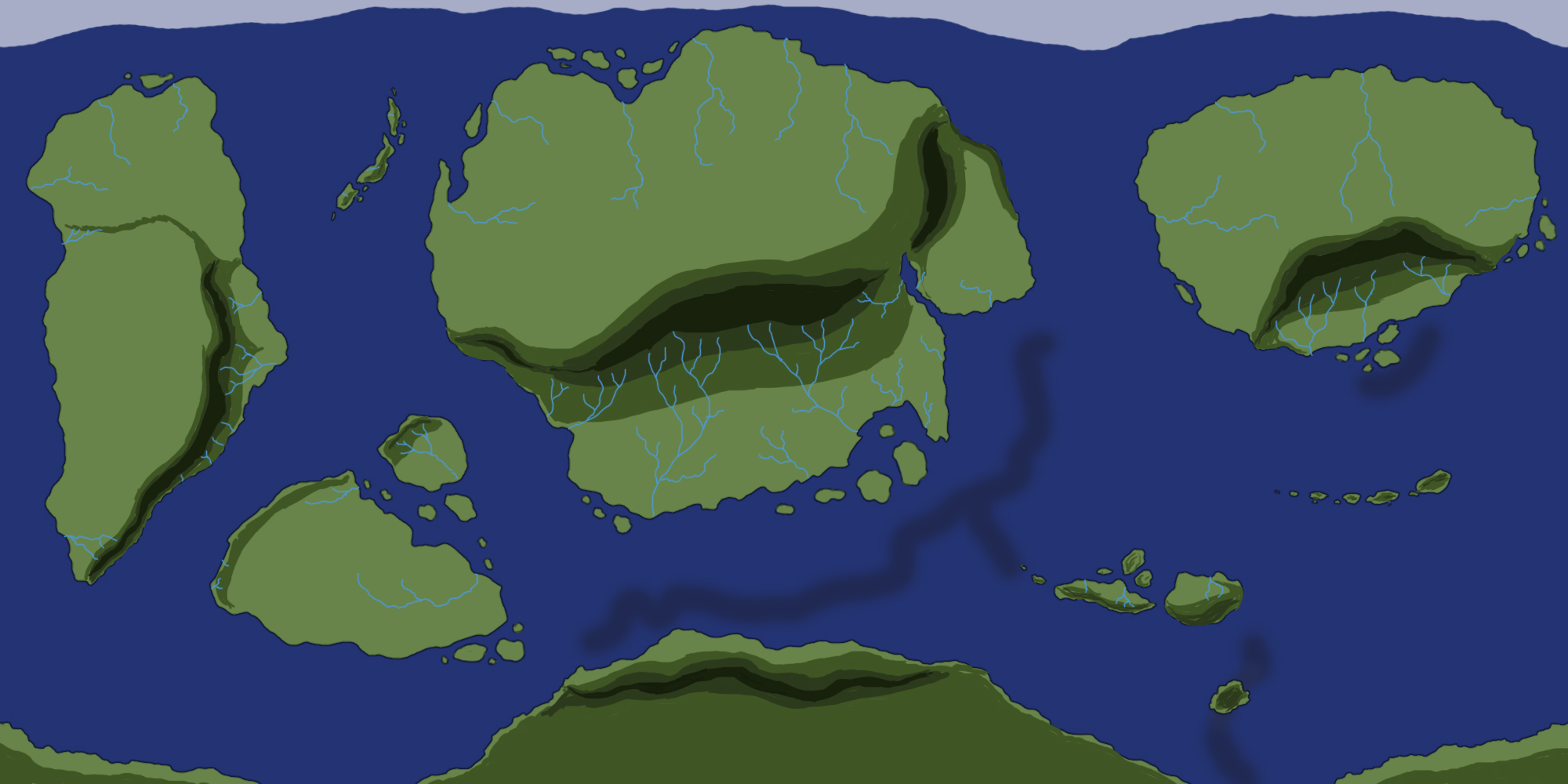

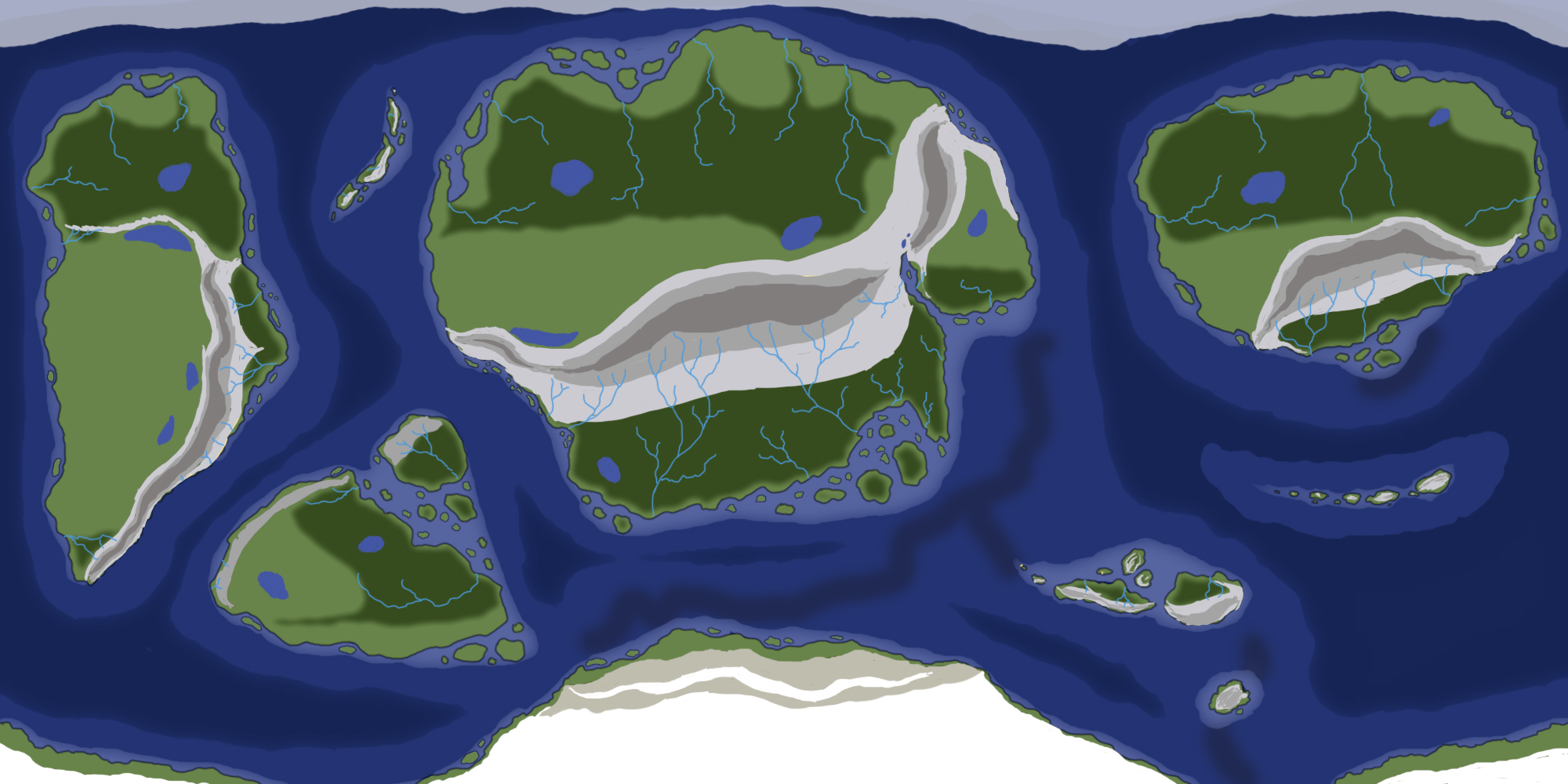

Note that in the image below the lakes within the deserts are dry outside of the rain season.

The other type of lakes, the ones with outflows (exorheic regions), come in various forms. A few forms you may like to include on your map are:

- Volcanic/crater lakes (can be endorheic too). Lakes within volcano tops, but could also be lakes within craters created by meteorite or asteroid impacts.

- Glacial lakes come in different forms. One such form is the erosion of topsoil until bare rock is all there's left, creating a very irregular surface and resulting in countless lakes, like in Canada and Finland.

- Subglacial lakes are lakes locked under a glacier. They form as a result of immense pressures between bedrock and the ice on top. This pressure decreases the melting point of ice, creating a lake underneath the thick ice.

- Rift lakes are regions where tectonic plates separate. This separation can result in relatively temporary depressions which rain could fill. Eventually they join with the ocean as the plates continue to separate.

For map creation purposes you can add lakes wherever you wish as long as they follow logical rules. You wouldn't have glacial lakes in a desert, for example. But adding smaller lakes often means you're getting into the finer details of map creation, which can make things look odd when other parts don't have the same amount of detail. So, for now, I recommend only adding the biggest and most (story) relevant lakes and leaving out others until later down the line when we'll add finer details.

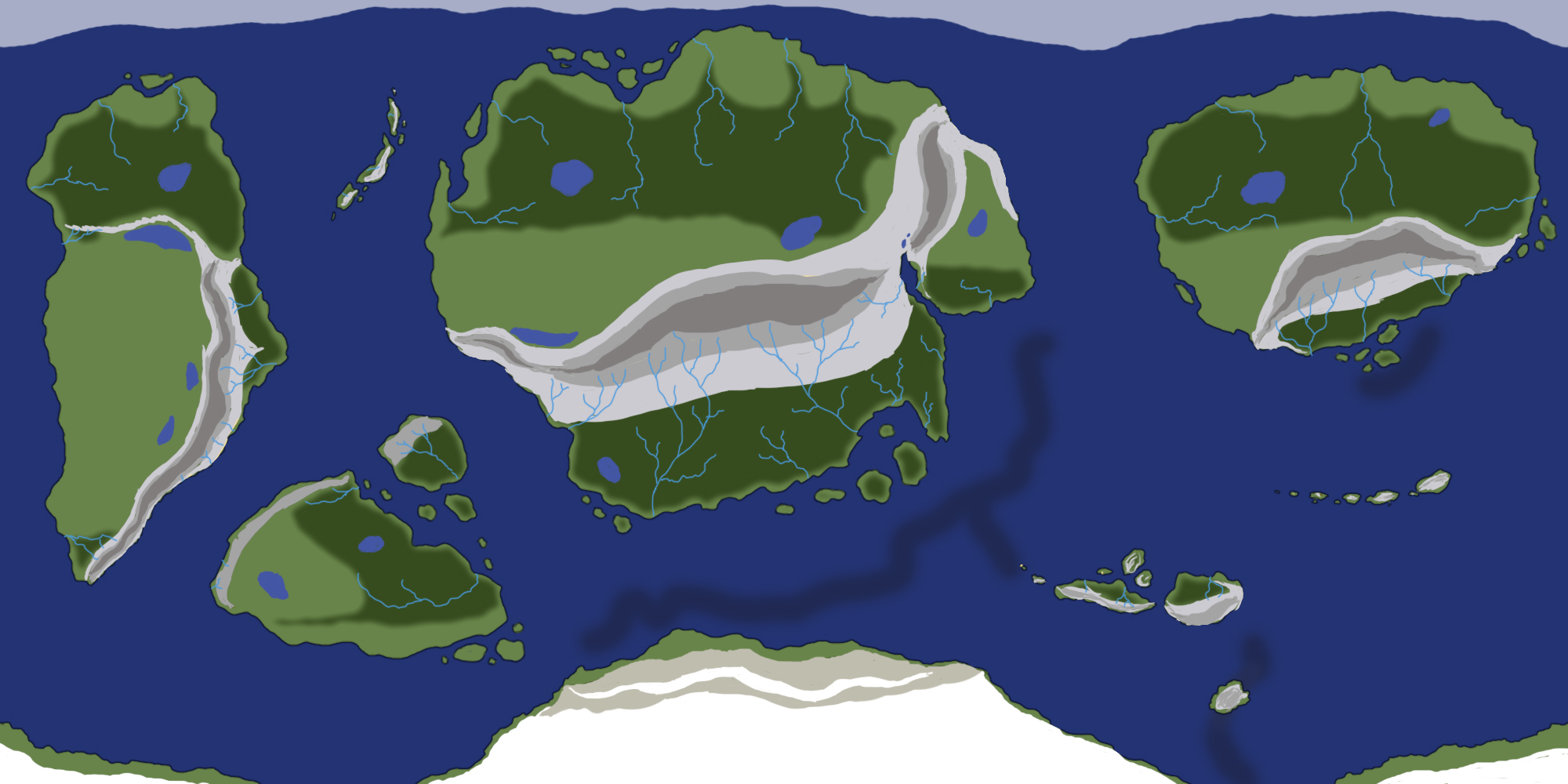

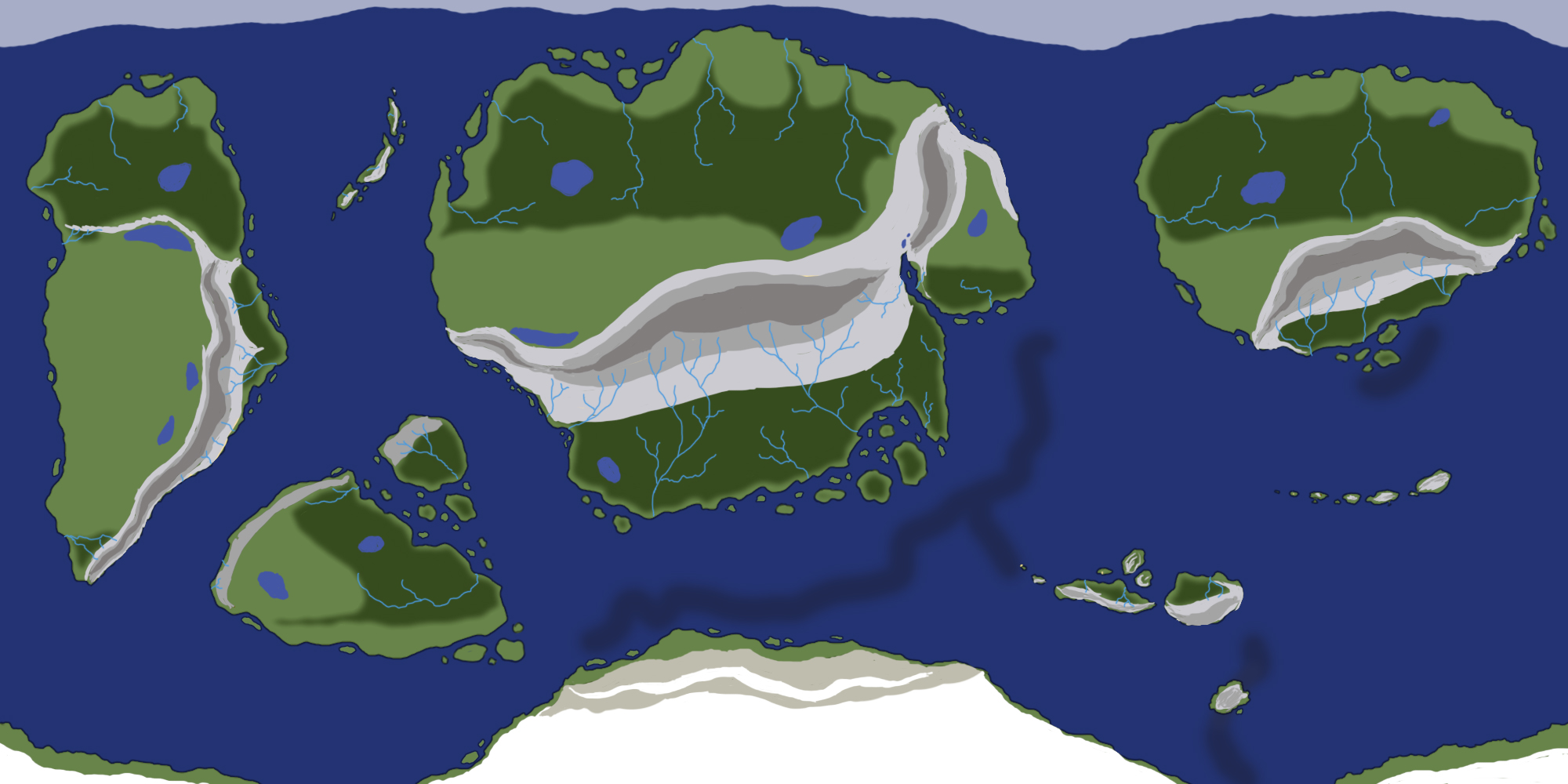

I've added some more lakes to my map (see below), but I consider them place holders for either big lakes or lake-rich areas for when I get to the finer details stage where I will refine them.

Other water bodies & features

Most water features aren't really visible on maps when we're working at the current scale. So I'd leave them out unless they're of importance, and perhaps keep them for their own, individual maps of their area rather than the world as a whole. But here are where you'd find some prominent water bodies/features nonetheless:

- Oases: Found on the lowest parts of deserts. Underground water collects from a huge area around it and pools into this tiny area. Water levels will vary greatly depending on how often rain falls in this region. They're often small, so might not be worth adding to the map.

- Waterfalls: Anywhere with steep cliffs and enough water. I'd focus only on big waterfalls, as there are countless small ones all over the world. I'd also leave waterfalls until the finer details stage, but you can make a note on your map to remember a potential position.

- Deltas: At the end of rivers in regions with calm waters. If there are enough waves, the sediment deposited by the rivers will carry the sediment away and keep the river looking like a singular exit rather than the forked one at deltas. Rivers must also flow slowly and carry enough sediment to be deposited.

Note that deltas are incredibly fertile and thus incredibly valuable for agriculture. This could be of significance for your story universe.

- Glaciers: Essentially just show up as snow, so not really worth adding to a map in any significant way unless of relevance to a story. Even then a simple name tag will often do.

- Mangroves: See biome description above. I'd leave them out (perhaps only for now) unless they're huge and/or of importance.

- Swamps: Freshwater ones are usually found alongside rivers and flood seasonally with enough rainfall. Saltwater ones are found along (sub)tropical coastlines. In both cases their soils are saturated with water, and water moves slowly.

- Man-made features: If big enough (like some canals), you can definitely add them now. Dams can also drastically change rivers, essentially creating a lake and may be worth adding if the lake is big enough (like in some hydroelectric dams).

Mountains

We've already added a rough version of the majority of our mountains in the tectonic plates stage, but if you need/want more mountains in specific regions of your world, you can still add small plates to add smaller mountain ranges or by mimicking the Scandinavian Mountains like I mentioned at the end of Part 1 of this guide.

Since I'm personally happy with the mountain ranges on my map, I won't be adding any new ones.

Note that we'll change the design of the mountains in a later part of this guide, so for now the current preliminary height map version will do and any mountains you may add can be added in a similar fashion.

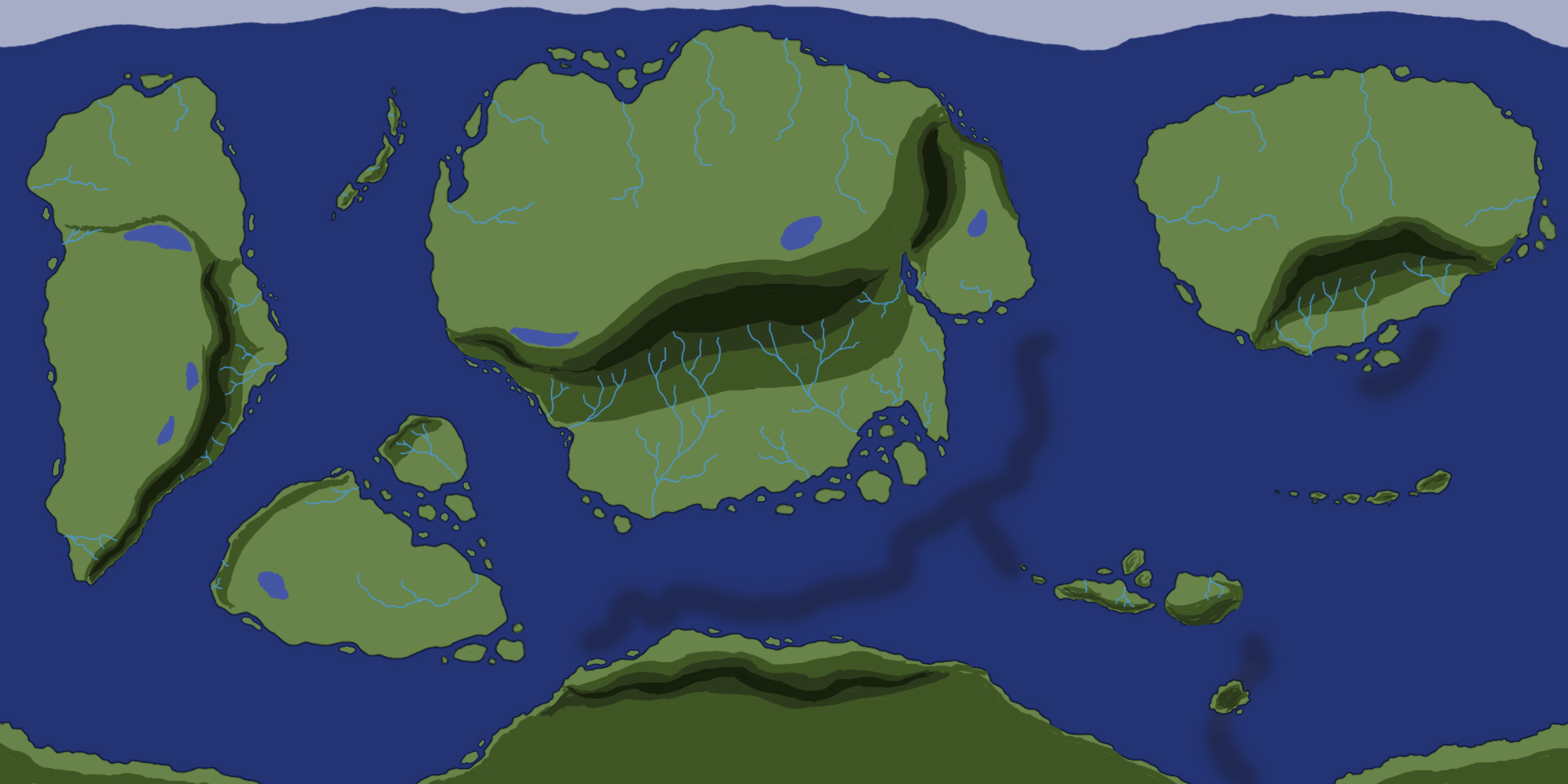

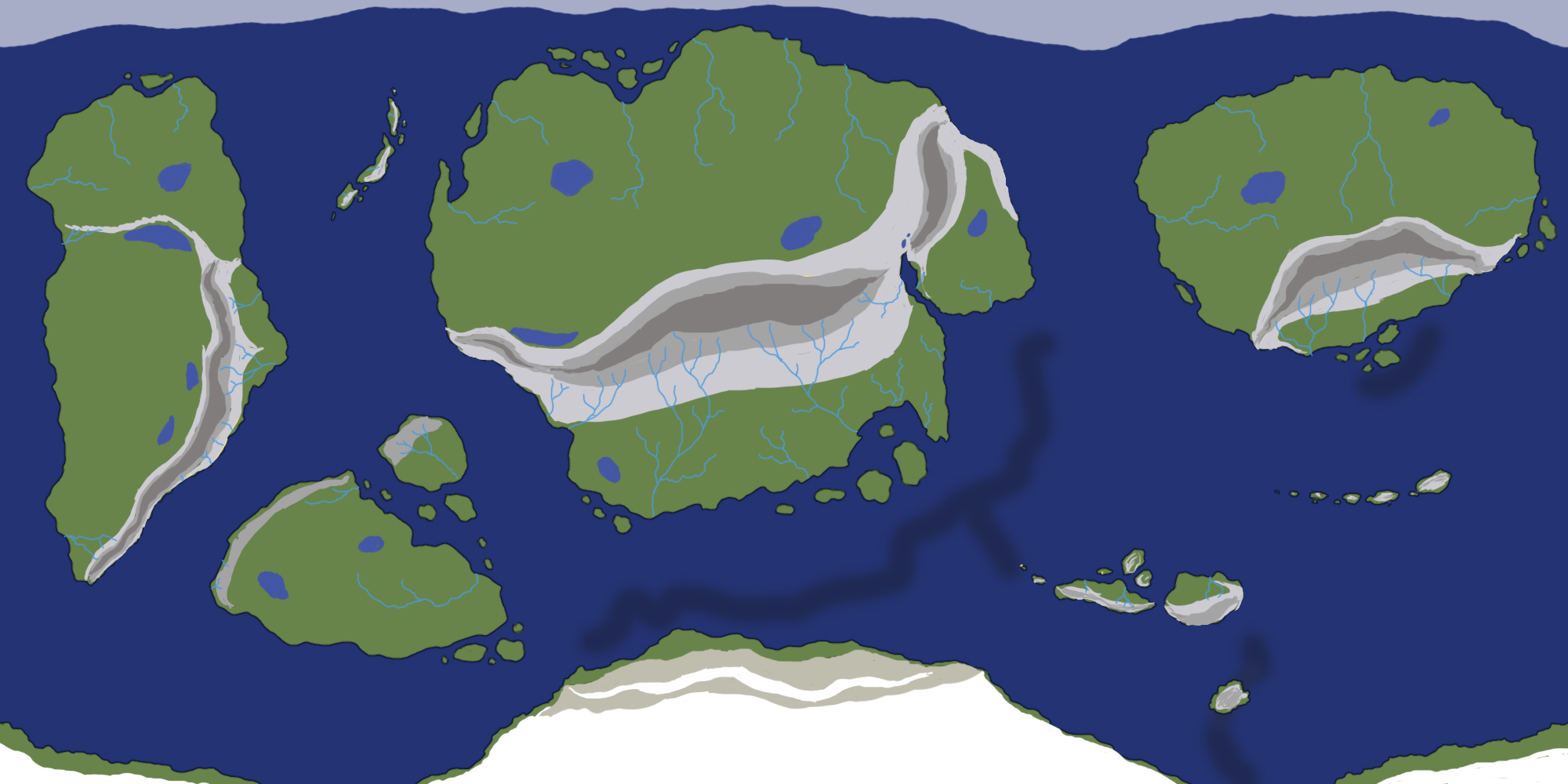

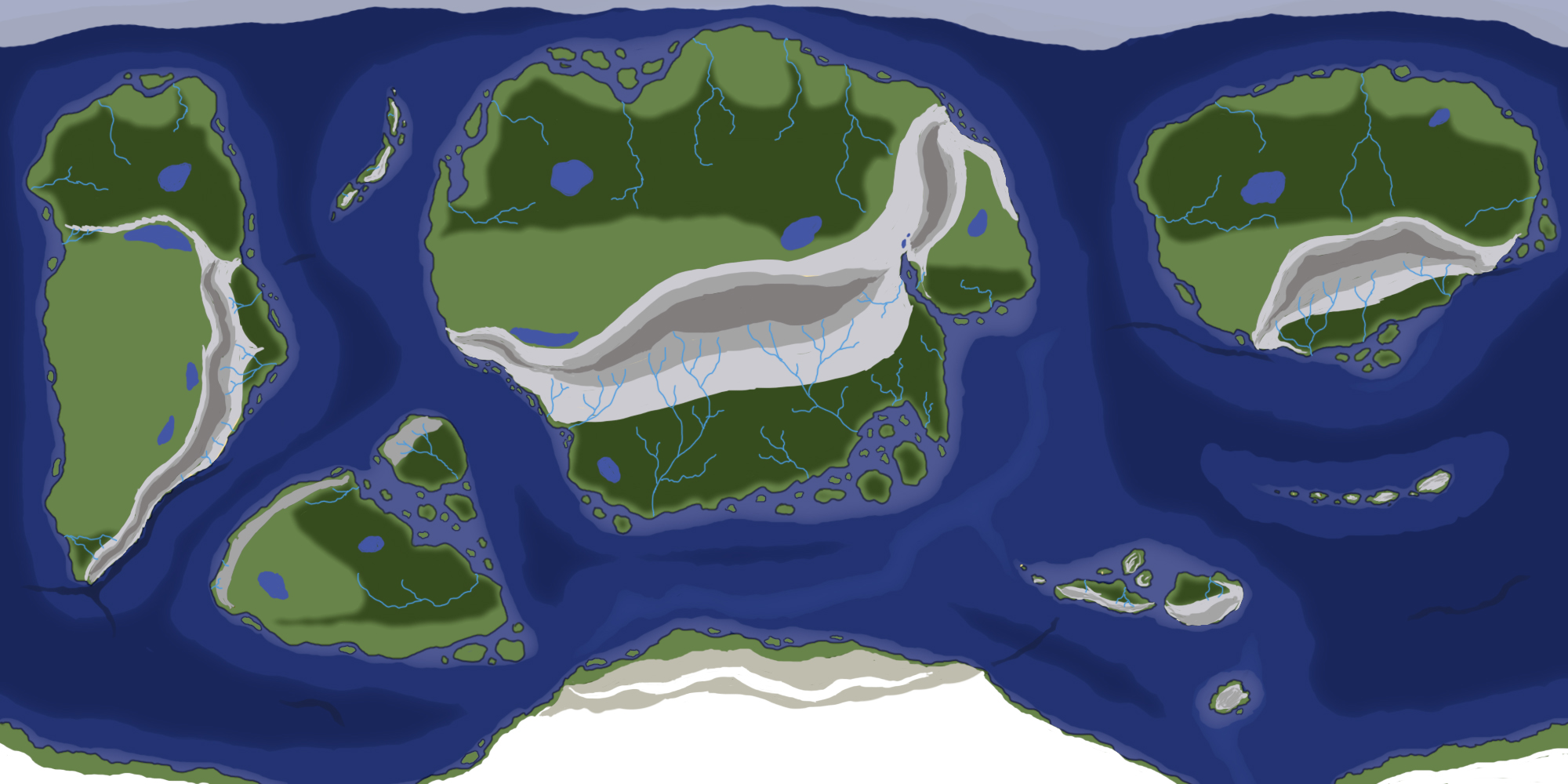

Having said that, one thing we can do right now is changing the color of the mountains so we can use the greens for forests instead. Alternatively, you could use many colors to mark different mountain ranges (forests vs bare rock, snow vs forested, etc.). Using the climate map we made before, this process is quite fast and simple for a quick guide version, but I'm sticking with a simple recolor for the most part. Only the southern continent gets snow on the elevated areas for now.

Other creative choices can be made now as well, like adding snow to extra high mountain tops in tropical zones, for example, or adding lava flows/pools on active volcanoes. Just simple representations will do.

Forests

Forests add lots of detail to a map, but they're best represented with at the very least some icons. They could be represented with detailed drawings too, or in a few other ways. I'll cover various approaches in the next part of this guide. So, as you probably already guessed, the brunt of the work comes in during the details stage.

However, we can add patches of green (or any color you wish) to mark where major forests will be. While entirely optional, it can change the look of your map drastically and make you see it in a different light. This in turn can help with planning out where you may wish settlements in the future, whether you want to change or add other features (like another river or lake) or whether you need more space because it turns out you need more space for a gigantic mega forest.

Caves & cliffs

These are also features you can leave out unless important to whoever uses the map. If they are, you can simply mark them on your map for now and replace the marks with a design of your choice in the design stage later in this guide.

Islands

If you want/need more islands on your map, there are three types of islands to work with:

- Continental islands

- Oceanic islands

- Tropical islands

Continental islands are islands who sit on top of a continental shelf. They could be leftovers from when two continental shelves broke apart, formed by a subduction zone, or, more rarely, the result of deposition of sediment and small rocks like in river deltas. The latter are always found along coasts and it's unclear how exactly they are formed. Examples can be found from Quebec all the way down the US' eastern coast and down to Mexico.

Erosion can also create islands along continental coasts.

Oceanic islands are generally the result of volcanic activity. The Hawaiian Islands are an example of this, but these islands don't have to be part of a chain, but tectonic movement usually results in chains over time.

Tropical islands are formed by the growth of corals. Corals will keep growing toward the surface and on top of debris, eventually leading to island formations. While this could technically happen outside of the tropics, they're most prominent in the tropics because of the growth requirements for most corals.

So with this in mind you can add islands just about anywhere you wish. Perhaps you need one for a castle off the coast or a chain of islands for a pirate hideout. Islands are easy enough to justify geologically, but I'd stick to only adding the bigger islands unless you plan on adding all the tiny islands that would naturally form all across your map. If you only add them in important places, the other areas will usually look odd due to the imbalance, but this is a subjective choice.

As you can see, I've added some smaller islands around the map. I mostly put them where I think they'll look good, but in other cases, like the western continent's new eastern islands, I added them for a the potential of more coral reefs and thus richer fishing waters for a small civilzation I may add in this region.

Extras

There are a lot more features you could potentially add, but they're far too numerous to mention all. Many are relatively small, so only worth adding to spice up a map with interesting features (the same way you'd find fantastical creatures on old maps) if you're going for a specific style or if these features are of significance. But looking into them can be helpful to make different regions of the world stand out from each other. This is mostly a story oriented approach though, as these features usually wouldn't be visible on a regular map. I'll cover many of them in the icon creation part of this guide though, so more on these later.

Aquatic Features

Now we'll cover aquatic (oceanic) features. They're not as numerous, but can drastically change the look of a map. You don't have to add these aquatic features, it depends partially on your own stylistic choices and partially on the purpose of the map and what universe it belongs to. Mapping of oceanic features depends a lot on modern technology, so a supposed map maker within your fictional universe might not have a clue about what the deepest depths of the oceans look like without access to this kind of technology.

Oceanic Plateaus

Oceanic plateaus are similar to abyssal plains, but are parts of the ocean floor higher than the surrounding floor and has at least 1 steep side (often a descent of 200 or so meters / 600 ft.) They're often part of continental crusts and, like abyssal plains, they're flat though not as flat as abyssal plains.

They also occur in "large igneous provinces", which are essentially places with a large accumulation of solidified magma and lava.

If the oceanic plateau is part of the continental shelf and near the coast, it may be home to corals if the requirements mentioned earlier in the biome section are met, though oceanic plateaus are usually found below the 50 meter (160 ft) maximum depth for most corals.

On your map, you can outline your continental edges with a light color to mark the oceanic plateaus. You can extend them quite far at some points, like the oceanic plateau in New Zealand, and play around with the shapes a little to make things look more organic.

Abyssal Plains

Abyssal plains are the gigantic, incredibly flat surfaces found deep in the ocean. They're usually found between the foot of a continent (where it comes out of the water) and a mid-ocean ridge (where tectonic plates separate and mountains form through the lava breaking through this split).

They're usually found between 3000 and 6000 meters (10,000 and 20,000 ft) deep and on Earth are most common in the Atlantic Ocean.

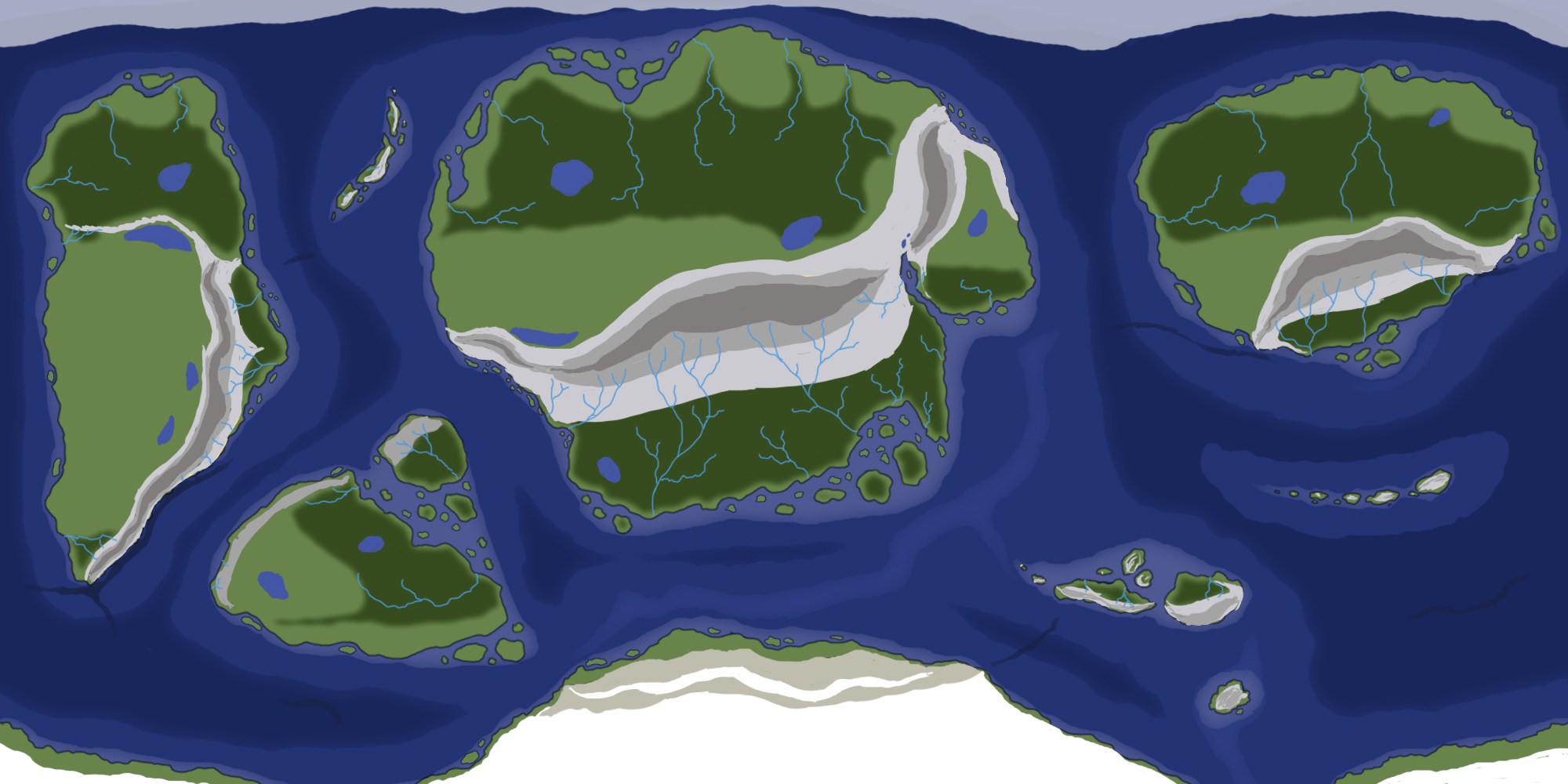

If you want to add them to your map, you can simply color all the oceans a darker color and leave a thick margin around continental edges and oceanic rifts. If an oceanic rift is close to a continent, you don't need to add an abyssal plain, as shown in the image below in the southern part of the map.

We'll make it look better in the detail stage.

For historic reference, the existence of abyssal plains weren't discovered (recorded) until the end of the 19th century. But much remains to be discovered about them.

Mid-Oceanic Ridges

Oceanic ridges are mountain systems formed underwater wherever the seafloor separated due to tectonic plates moving away from each other. I already marked these zones on my map in part 1 as a darker blue color, but have re-marked them with a lighter color below to mark the difference in height compared to the abyssal plains around it.

Oceanic Trenches

Oceanic trenches are the deepest parts of oceans and are found where one plate dives under another during their collision. Since these plate borders are often home to volcanic chains as well, oceanic trenches often run parallel to these volcanic chains or at least mountain ranges. On Earth, the western coast of South America is a great example of this.

On my map, the left continent's border has an oceanic trench, and I can add more trenches wherever one plate dives under another within the ocean. Note that you can play around with the age of this collision to a degree to make the trenches deeper, more or less stable, and so on.

Also note that these areas are one of the ways a tsunami might occur as a result of this collision (and assuming the resulting wave can travel far enough to trigger a tsunami). So any far enough shore in direct line of these points could have a tsunami threat.

Adding them to the map is as simple as drawing a darker line along any collision zone in your ocean. If the collision is relatively new, you can leave it out.

We'll make these trenches look better in the details section as well.

Coral reefs

For our map creation purposes, you can mark where corals would likely grow as a reference point for when you wish to use it in a story for example, or when figuring out what the people in your world would've been able to eat during their history.

The points they'd likely grow are in tropical zones (between 30 degrees north and south) and in waters with few nutrients. This means away from western coasts with large open oceans, as these often bring colder waters through upwelling. It also means away from large rivers, as their freshwater changes the saline conditions around them.

In my world it mostly means the zones found in the map below. Keep in mind that you can find some coral species further away from the equator, so you do have some creative freedom to add corals elsewhere.

While very rare, you do find corals on the western coasts of Africa and the Americas, for example.

If coral reefs aren't of importance to your story, the only ones you may wish to mark are the gigantic ones like the Great Barrier Reef, which are visible from space. But this is a stylistic choice and perhaps one left for the details section.

Next up: Making it look good

We've now laid solid foundations for our map and I know it doesn't look great, but remember: this map is full of placeholders. In the next part we'll delve into making our map look good and I'll cover multiple styles from super simple to more advanced techniques.

In later parts I will likely also go over the human element, from trade to civilizations to expansions and so on. Though I may put these in a linked sub-guide instead, which will allow me to add more guides like it in the future. Those guides could include more in depth biome creation, animal movement across the globe, more world building, creating local gods, and so on. But let's not get ahead just yet, first the details part up next.